How to Make Winning Decisions

Updated Feb 25th, 2025

For every complex problem, there is a solution that is simple, neat, and wrong.

Henry L. Mencken

The significant problems we have cannot be solved at the same level of thinking with which we created them.

Albert Einstein

Introduction

Obstacles are those frightful things you see when you take your eyes off your goal.

Henry Ford

When all you have is a hammer, everything looks like a nail.

It has been said that insanity is doing the same thing over and over

while expecting different results. I assume you are reading this because

you want different results. Perhaps you make decisions based on the

same types of information, discussion and analysis. Perhaps you are wondering when you will see the

different results you want.

What follows may be quite different from what you’re used to. Set

aside your preconceptions, take your time, and enjoy the ride.

Can you think of a time when someone made inaccurate claims, perhaps

out of ignorance, to shift blame, or to win an argument?

Can you think of a time when someone didn’t seem to care about your

concerns before making a decision you didn’t like? Perhaps this person

listened briefly before interrupting to lecture you, or tell you that

you’re wrong, or how you should or shouldn’t feel. Perhaps this person

misunderstood your concerns or didn’t want to understand. Perhaps your

concerns were dismissed as not important enough to change the decision.

Were you expected to just accept that it’s over and there is nothing you

can do?

If the above situations seem familiar, is there anything you’d like

to change?

I’ve worked with groups of 15-20 maximum-security prisoners

consisting of different races, cultures, education levels and economic

backgrounds. After learning some fundamental communication,

problem-solving and conflict-resolution skills, the groups have

respectful, constructive discussions and make unanimous decisions.

People learned to be careful about what they put in their

stomachs by considering nutritional value as well as taste or convenience. They can

learn to be at least as careful about what they put in their minds by

considering facts, reason, and consequences as well as emotional comfort or fear.

I hear and I forget. I see and I remember. I do and I understand.

I encourage you to

"do" this website. When you come to a question or incomplete statement,

think about it. Whether you share your answer with anyone is up to you.

If no answer comes to mind, share your goals and concerns rather than

giving up or asking

someone for an answer. Exploring possibilities with others may help

you clarify your thoughts, ask different questions, and discover your own

answers.

If you don’t know where you’re going, any road will take you there.

If you do what you’ve always done, you’ll get what you always got.

The devil is in the details.

The road to hell is paved with good intentions.

Any road also works if your destination is "not here". How will I

know I’m there if I don’t know where "there" is? Before I jump on a

bandwagon, I like to know where it’s going, who’s driving, and how

bumpy the ride could be. Before considering potential solutions, I like

to have a clear understanding of what I hope to accomplish and how I will know I am done. This helps

me choose an appropriate solution and helps me check for possible

unintended consequences.

Think about the questions in the introduction and imagine what might

change if you get everything you asked for.

If you responded to anything in the negative, such as listing things

you don’t want, think of everything in the world that isn’t that. If

you tell a child not to hit, does that mean biting or kicking is

OK?

If you’re not sure how to express what you want but think you’ll

know it if you see it:

-

What if you don’t see anything you like?

-

What specific observations do you like or not like? Why?

-

Could there be lurking unintended consequences?

-

How many successful outcomes would you need to see to be

confident that the next outcome will also meet your goals?

Feel free to make any needed adjustments. If you’re satisfied with what you’re doing,

thanks for stopping by. If not, please keep

reading.

Why all these questions?

According to an old adage, a free fish feeds someone for day but fishing lessons feed them for life.

We could also say that giving people a solution might satisfy them for a day, or perhaps

start an argument lasting much longer. Helping people find their own solutions

could satisfy them for life. Accepting a solution provided by someone else

might seem comforting, but blindly following may have unpleasant

consequences. Once people become invested in a specific solution it is much

more difficult for them to see alternatives.

If you start by choosing a destination, you can choose from

several possible routes, and are free to change routes along the way. If you

chose your destination well, you will probably like where you are. If not, you are

free to choose another destination.

Why not just debate a specific proposal?

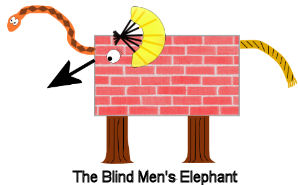

Consider John Godfrey Saxe’s poem

"The Blind Men and the Elephant".

We could try to

settle the blind men’s dispute with a debate followed by a vote by the audience. Each blind man

could make his case, summoning all the eloquence he can muster and supporting

his position with the "facts" of his observations. This approach

might produce a "winner", but does it determine once and for

all what an elephant really looks like? Should textbooks use this description

of elephants?

I prefer a system where people clarify shared goals and needs

before becoming invested in a particular solution. I benefit by learning from

others and by looking for something useful in the positions of others. Taking

ideas from various positions may lead to a new option that better meets the goals of everyone.

If you are inclined to evaluate one specific proposal at a time, a good

place to start is with your own position. What inspires you to reconsider or

shift your own position? How well does your current preference meets your own

goals and the goals of others who prefer a different option?

Fundamental Principles to Help Get Started

-

Learn by experiencing the process.

-

Individuals seek, explore, and reconsider with guidance from peers.

-

Listen without judging.

-

Be open to learning from others who may be different.

-

Present your own position firmly but fairly.

-

Take the advice you offer others and be a good example.

-

Look for the good within yourself and others.

Think back to the opening

questions about your own past experiences and what you want to be

different next time.

Offering others options such as considering the needs of others

before acting, exploring alternatives, or re-considering

beliefs that lead to harmful actions may be part of the solution but the person I can influence

most is myself. I have a few guidelines that I adjust for each

situation.

Each was partly in the right, and all were in the wrong. How can we

be certain that we know enough?

I will assume that those who disagree know something I don’t

I believe that we know more than me. I will ask questions and be

willing to shift my position as my understanding deepens. I will focus

on the other person as they express their own motivations, goals,

thoughts or emotions. If I notice myself looking for an opportunity to

jump in and respond, correct, or criticize, I will recognize that my

attention is drifting from the other person to myself.

Being offended, or assigning fault or blame to others, does not

automatically make me right. I will offer to explore

solutions together in the hope that we can both be right.

I will distinguish between observations and interpretations

If I see someone waving her arms near a toad, before jumping to the

conclusion that she’s a witch who just turned someone into a toad, I

will remember I only observed that she’s waving her arms and there’s a

toad nearby. Perhaps she’s conducting a symphony she composed for the

toad. I won’t know for sure until I ask. While pursuing a specific

goal, people sometimes make decisions that harm others. I could assume

the intention was to harm others, or that this person doesn’t care

about others. I could also ask about the problem and offer to help

explore ways to achieve the goal without harming others.

I will distinguish between goals and game-plans

People share goals or needs such as food, air, water, life, liberty,

and the pursuit of happiness. To meet their goals, people

might explore various game-plans, or solutions, such as buying food, exercising, or

meditating. Spending money is a common game-plan. Before discussing

game-plans such as how much money to spend, I like to consider the

actual goals and other possible game-plans to meet those goals.

I will look at short-term needs and long-term needs and recognize

that different game-plans might apply to each. Long-term goals of a

starving village might be met with seeds to grow food. Villagers also

need to survive long enough to harvest the first crop, which

requires a short-term game-plan other than eating the seeds. Will the

short-term game-plan lead naturally to the long-term game-plan or make

the long-term game-plan more difficult? How does each possible

game-plan bring everyone closer to their goals?

I will speak for myself

Sometimes I have an internal response such as "that’s stupid".

Before blurting out something I might later regret, I try to slow down

and think about what I hope to accomplish. If others do something that

I interpret as stupid, will calling them stupid make them smarter? Are

the others likely to thoughtfully consider my insult, decide I’m right,

and instantly change? Will finding fault with someone else make me

right, or is it possible we’re both wrong? If limited options lead to

slow progress and feelings of frustration, I could say that I’m

experiencing frustration over the limited options and invite the other

person to join me in exploring new options.

Observations, interpretations, goals, and game-plans may all be

jumbled together in someone’s mind. What I consider a factual

evaluation of an interpretation or game-plan could be heard as an attack on a

cherished goal, leading to a defensive response and a higher wall

between us. Until I understand and acknowledge the goals of others,

comments about interpretations or game-plans may just bounce off, increasing the

frustration level in both of us. Recognizing and understanding these

concepts in myself makes it easier to recognize and deal with them in

others.

Easier Said than Done

We all know how others ought to behave and how others need to change. Taking our own advice

is a process and a journey. We won’t always get it right the first time. It’s important

to be careful how we point out lapses by others, and hope they do the same for us.

We know more than me.

What about voting?

-

Will a vote end the controversy?

-

What if someone doesn’t like any of the choices offered?

-

If there are more than two choices, each individual choice may

get less than half the total vote. How much support should the

winning option have?

-

Should math students vote for their favorite solution to an

equation?

-

Should 2 wolves and a lamb choose lunch by voting?

What about negotiating?

-

Will trading concessions make everyone more satisfied?

-

Will splitting the difference get people what they need?

-

If we agree to disagree, is the controversy over?

-

If everyone is equally upset, have we found the best solution?

What about lectures or speeches?

-

Will manipulating opinion solve the problem once and for all?

-

How do you know if the information is correct?

-

How many different perspectives are needed for a complete understanding?

-

How do you know when you’ve heard enough to make an informed

decision?

Groups can find solutions acceptable to everyone in the group. When

I’m satisfied with a group decision, I’m more likely to help make it

work and more likely to consider the problem solved. If I’m on the

losing side of a vote, or I’m limited to choosing between unpleasant

options, I may look for ways to keep the controversy alive after the

vote is over. Making decisions as a group may take longer

but could solve the problem sooner. As with voting, negotiating or debating , some

people may choose not to participate. Perhaps they do not have a strong preference, or they are confident that another

participant adequately represents their position.

Think back to the opening

questions about your own past experiences and what you want to be

different next time.

1: Explore the Problem

Listen to everyone’s goals or needs and try to see the problem from

each individual’s perspective. If I notice myself wanting to jump in

and respond, correct or criticize, I consider that a warning that I’m

focusing on myself when this first step is about understanding the

needs of others. We could mention short-term

needs and long-term

needs if they are different. Focus on goals.

We look at game-plans

later. We could also consider the qualities or

characteristics of each person's ideal solution.

Are some qualities or characteristics more important than others?

2: Look for Common Goals

Think about which goals or needs everyone

shares. This is a chance to release your inner 3-year-old and

relentlessly ask "why?" Why do I need ___? So I can do ___. Why do I

want to do ___? What will happen if I don’t do ___? If I do ___ then I

___. You may end up with a basic concept such as survival, safety,

shelter, liberty, happiness, inner peace, or social interaction.

3: Identify Resources

Make a list potential resources such as money, time, materials, paid staff and

volunteers. Stop when you cannot think of anything else for the list. You can add things later.

We look at how these resources might be used later.

4: Create a Solution Smorgasbord

List potential game-plans. This is an opportunity to expand our options

before making a commitment to a specific game-plan. Look for

opportunities to split proposals into smaller pieces and combine the

split pieces in various ways.

5: Evaluate Each Potential Game-plan

Allow each person a chance to comment on the possible game-plans. This

should be the first time you consider the merits and potential problems

of any game-plan. How well does each game-plan meet the

stated goals? Look for ways to shorten the list by

combining game-plans that have much in common. If people seem committed to contradictory game-plans,

take a step back, review the goals, and work backwards from the goal to a suitable game-plan.

Keep evaluating until everyone is satisfied.

6: Decide How to Make It Work

Who, what, when, where, how? If people are convinced there is no way to

make the chosen solution work, review the previous steps.

Review

Do an occasional check-in to see how the agreement is working and look

for unintended consequences. Repeat previous steps as needed to make

changes or corrections.

I Believe, Therefore I Am

What we need is not the will to believe but

the will to find out.

Bertrand Russell

Loyalty to a petrified opinion never yet

broke a chain or freed a human soul.

Mark Twain

We can easily forgive a child who is

afraid of the dark; the real tragedy of life is when adults are afraid of the

light.

Plato

Many think of their beliefs and opinions as part

of who they are, but what about the

way they formed those beliefs and opinions? Before we were believers, we

were blank slates capable of forming beliefs. The philosopher Descartes went so far

as to doubt his very existence. He finally concluded that if he could doubt his

existence, think about his doubt, and even doubt that he was thinking about

doubt, then he must actually exist. He simplified his conclusion to, "I

think, therefore I am." Before thinking about something you believe and

how that belief is part of who you are, think about how you came to believe it.

Was there ever a time you believed something

different? If so, what changed?

If you believe because someone told you to

believe, would you change your mind if the same person now told you to believe

the opposite?

If you believe because you "just know"

it’s true, what would you say to someone who "just knows" it’s not

true? How would you respond if someone says the same thing to you?

If you believe it’s true for you, could it be

false for someone else? How could you tell if it’s true for someone you just

met? Is there a test for this

belief?

If you believe because it’s the only thing you

know, how would you respond to someone who knows more than you and believes

differently?

If you evaluate various options and try to choose

the best one, how do you respond to new information?

When people comment on your clothing, they are

probably also thinking about your taste in clothes or the way you choose your

clothes. The clothes themselves just hang on your body. The way you choose your clothes reflects

your personality. In the same way, why you believe and how you respond to those

who believe differently define you even more than what you believe.

On the Shoulders of Giants

If I have seen further, it is by standing

upon the shoulders of giants.

Sir Isaac Newton

Becoming part of the big picture doesn’t

make you smaller, it makes the picture bigger.

Many ideas grow better when transplanted

into another mind than in the one where they sprang up.

Oliver Wendell Holmes

Learn from the mistakes of others - you

can’t live long enough to make them all yourself.

Martin Vanbee

We humans are sharers and learners. We add our

own thoughts and creations to what we learn from parents, teachers, friends and

mentors, and then pass our knowledge along to others. 30 years after the

invention of the transistor, several manufacturers offered affordable home

computers. The Internet and spam were close behind. The first space shuttle

launch was less than eighty years after the Wright Brothers first flight. We cannot

all be rocket scientists or invent something as important as transistors, but

we can enjoy the benefits and share in the accomplishments by understanding to

the best of our ability.

Ideas and understanding evolve too. Thoughts about social hierarchies, entitlements, punishments, and how to treat those

who are different have changed much throughout human history.

Anyone can climb onto the shoulders of a giant. Some

offer their own contributions and others just enjoy the view, courtesy of those who came before.

Many people honor their heritage by passing on

the traditions of their culture or society. You can honor your heritage and also embrace change. Each

tradition came from somewhere and took its place alongside earlier traditions.

Our ancestors kept traditions because they served some purpose, even if that

purpose is simply to remind us of someone or something from our past. As we sit

on the giant of our own heritage, that giant can join others on the shoulders

of an even larger giant. We can climb ever higher without leaving anything

behind.

The Committee’s Camel

A camel is a horse designed by a committee.

Some compromises seem reasonable or innocent but may produce a bad decision (and a stubborn,

humpbacked, spitting horse).

-

Going along to get along

-

Splitting the difference

-

Swapping favors

-

Voting for one of two choices

Other, less innocent factors may also sneak through.

-

Self-interest of an individual, or a represented group

-

Ignoring potential consequences

-

Overlooking more fundamental issues

-

Combining several unrelated issues

After a lengthy discussion about how many eyes and ears a horse needs, some committee

members might say, "We went along with you on two eyes and two ears, so now you have to go along with us and give the

horse five legs". It should not be a matter of one person going along without question. Ideally,

everybody should agree with whatever is most beneficial to the horse, or the horse’s owner. There are valid

reasons for giving a horse two ears and two eyes, but much less compelling arguments for a five-legged horse.

How much should a horse eat? Some committee members say five pounds of oats per day, others say

eighty. It might seem tempting to split the difference, or vote for one or the other, but how does either choice benefit

the horse or the horse’s owner? Some say a horse that only eats five pounds of oats will be cheap to feed. Others say such

a horse won’t be strong enough for many jobs, and still others say a horse that eats lots of oats will boost profits

for farmers. If the committee really wants to stray from their

horse-designing mission and help farmers, there may be better ways that have nothing to do with feeding horses. These

are two separate issues that should be discussed separately. More importantly, why even discuss how much a horse should

eat? Food is basically an energy source. Once the committee determines how much work to expect from one horse,

nutritional requirements should follow easily. Those needing more power can use several horses together. Those who only

need the power of one horse should not have to buy excess oats.

Sometimes unavoidable ambiguities make agreement difficult. Carefully considering potential

consequences can become important. Some questions to ask are:

-

What are the consequences of being wrong?

-

Are we giving up something important to gain something else?

-

What are likely early warning signs?

-

How easily can we respond to those warning signs?

-

What sorts of corrections can we make as things develop?

-

What safety precautions or intermediate steps could be taken?

-

If it turns out we made a bad decision, how easily can we change it?

Members skeptical of the solution might be assigned as lookouts for signs of trouble.

Some committee members might represent a larger group and vote according to their group’s

desires. These representatives should present the concerns of their group to the entire committee, and help the

committee understand and consider those concerns, but vote in the best interest of the committee’s objective. If the

final decision conflicts with the group’s initial desires, the representative can help the group understand why the committee

made that decision and how everyone benefits.

Traditional "yes/no", "one-or-the-other" voting works if

there are only two reasonable options. If there are more than two options, Ranked Choice Voting is much more flexible.

Let

it Begin with Me

Take care when giving advice. It might be given back.

I think I’d better think it out again.

Fagin’s song "Reviewing The Situation" from Oliver

It has been said in many ways:

Let him that would change the world,

first change himself!

Socrates (470BC - 399BC)

O would some power the gift to give us

to see ourselves as others see us.

Robert Burns (1759 - 1796)

Everyone thinks of changing the world,

but no one thinks of changing himself.

Leo Tolstoy (1828 - 1910)

You must be the change you wish to see

in the world.

Mahatma Gandhi (1869 - 1948)

Everything that irritates us about others can lead us to an

understanding of ourselves.

Carl Jung (1875 - 1961)

We have met the enemy and he is

us.

Pogo/Walt Kelly (1913 - 1973)

Ask not what your country can do for

you, do it for yourself.

Stewart Brand (b.1938)

It is about admitting to ourselves that we have much more in common

with others than we would like to admit. For many, this is the most

difficult part of the process.

It may be tempting to think that everything would be fine if those others would

stop being so stubborn, admit that they are wrong, and agree to do things my way. Those others

may be thinking the same about me. We may settle for splitting the difference,

trading concessions, or simply agreeing to disagree. What if, like the blind men and the elephant,

we were both wrong from the start? If we are going

to break the cycle, someone has to go first.

Many people who have listened to a foreign language

may have heard words in the other language that sound like words in English.

The foreign words may sound familiar but could have very different meanings and

the consequences can vary from humorous to catastrophic. If people have nothing

else to go on, it is tempting to jump to conclusions based only on that little

bit that seems familiar. We need to remind ourselves to slow down and ask

questions before acting on something that may exist only in our imagination.

People often enjoy stumping each other with riddles and brainteasers that may rely on

steering people toward a wrong path, dead end, or contradiction.

The solution often requires backing up to the wrong turn

and taking a different, less obvious path.

Murder mysteries may

begin with clues that point to a particular suspect. Other characters

may demand this person be immediately arrested and punished. The true culprit is only revealed after a

determined detective sees some troubling loose ends and digs deeper. It is easy for readers or observers

to simply enjoy the bumps, twists, and turns of a well-told story without becoming emotionally invested in a particular outcome.

Situations that impact us directly are more difficult, but it is still important to occasionally take

a step back, listen to others, and look for alternate paths that may lead to a different conclusion.

There is a game where people pass a

message around a circle by whispering in the ear of the next person.

By the time the message gets around the circle, it is often changed.

As a message travels from our ears to our

conscious mind, it travels through various pathways controlled by our thoughts,

feelings, preconceptions, knowledge, past experiences, or associations with

other concepts. Some pathways are straight. Others

may have twists, bumps, trap doors or dead ends. While traveling through an

internal pathway, the message may change, or part of the message may be trapped

or erased. As we become aware of these pathways and observe messages passing

through, we can learn to straighten out crooked pathways, seek shortcuts, and

create new pathways. One way to explore our internal pathways is to observe

ourselves thinking. This leads to a better understanding of our own thought

process and the various associations we make.

Think back to the opening

questions about your own past experiences and what you want to be

different next time.

-

I accept something as true when ...

-

I know I am getting good advice when ...

-

I trust people who ...

-

I accept the decisions or opinions of others when ...

-

When meeting someone new, I think about ...

-

As I get to know someone, some changes in me are ...

-

Something I would like others to know about me is ...

-

Something surprising I learned about someone else is ...

-

Some ways I respond differently to different people are ...

-

Something I value in others is ...

-

I accept the needs of others as equal to my own needs when ...

-

When I hear a rumor about someone I don’t like I ...

-

When facing 2 unpleasant options I ...

-

Conflicting opinions are never/sometimes/always helpful because ...

-

When I want someone to change, I ...

-

When someone expects me to change, I ...

-

I make the best decisions when ...

-

I feel good about a decision when ...

-

I consider a situation "good enough" when ...

-

I reconsider past decisions when ...

-

I am confident I found the root of a problem when ...

As we explore our own pathways, we also learn

how to listen and ask questions that help us understand the pathways of others.

As we learn more about the pathways within ourselves and others, we learn to

recognize actual needs,

and how to separate those needs from strategies that we believe will help us

meet those needs. We can learn to distinguish "feel-good" solutions

from "do-good" solutions. We can share what is going inside of us in

specific situations and listen to what is going on inside others. If we catch

ourselves wanting to jump in or interrupt with our own opinions, we can take

that as a warning that we are focused on what is going on inside us rather than

carefully listening to what is going on inside someone else.

Many people find it easier to relate to others who are similar in

some way. How do you know what you might have in common with someone

you just met? If there are obvious

differences , could there also be something positive you both

share? If you both like music but listen to different kinds of music,

you might look deeper and consider:

-

When do we listen to music?

-

Do we share a reason we like our favorite music?

-

How did we first learn about the music we like now?

-

How could we help someone else understand why we like this music?

-

When we first heard this music, did we like it as much as we like

it now?

-

What kind of music did we like before and what changed?

-

Do we expect to listen only to this kind of music for the rest of

our lives?

-

Was there an especially meaningful moment in our lives associated

with our favorite music?

Unless I am certain that the other person enjoys answering personal

questions, I might begin by briefly sharing my own thoughts as an

example of the type of response I’m inviting. I try to assure others by

my example that I will not ask something I am not willing to discuss about

myself. If the other person accepts my invitation to speak, I let them

know I am listening by my body language, eye contact, and giving them

time to fully express their thoughts. When they finish, I might repeat

something I found interesting or meaningful. If I am tempted to

interrupt and respond, correct or criticize, I consider that a warning

that I am thinking about myself when I should be learning about someone

else. As my understanding deepens, my options increase and I may shift

my own position in some way.

Being a good example and encouraging others to do the same is a process and a journey. We will not always get it right the first time.

It is important to be careful about how we point out lapses by others, and hope they do the same for us.

I did all that and it still doesn’t work!

Am I not destroying my enemies when I make them my friends?

There are three sides to every story: your side, my side, and the truth.

Robert Evans

Outside of science, facts rarely determine anything. Context determines everything, and it changes.

Connie Rice

The one who frames the issue wins the debate.

Discussion is an exchange of knowledge; an argument an exchange of ignorance.

Robert Quillen

Some discussions are like the horns of a steer. A point here, a point there, and a lot of bull in between.

It is harder to hate up close.

Sometimes, despite patient persistence, agreement eludes the participants.

Perhaps someone is blocking a solution just because they can. Perhaps people

just don’t want the system to work, or don’t want to go along with the process. Perhaps

some like things as they are and do not care that others are left out. Perhaps some hate

others more than they want a solution.

Remember this is a journey, not a destination. In many cases, you do not just flip a switch and then

everyone lives happily ever after. It is an ongoing process. A participant’s desire for an inclusive solution must be greater than their hate, fear, or greed.

If you are working with people who choose not to cooperate, are there others who might be more receptive or could influence those who choose not to cooperate?

What are the consequences for each participant if there is no inclusive solution?

There may be obvious differences, but any two humans likely have much more in common than DNA.

When people hate each other more than they want a solution, finding that common humanity is a big step toward resolving differences.

It is harder to hate up close. Could there be something positive you can both relate to, such as a happy childhood moment,

life-changing events, a mentor, role-model, or important life-lessons?

What inspires you to stick with a discussion? How could you help someone else find similar inspiration?

How long has this problem been festering? What are the consequences of abandoning the search for a solution?

Considering the time it took for this problem to develop and the severity of the problem, how much time should be spent seeking a solution?

Review goals, game-plans, observations, and interpretations.

If you hear an interpretation, you might ask for a specific observation

and consider other possible interpretations of that observation.

What are your goals? What are the other person’s goals? If you ask about a goal, and the other person

responds with a game-plan, you

might ask a follow-up question, such as "why is this important to

you?" or "what will happen if you do not do this?" Hopefully the

answer will bring you both closer to understanding the actual goal. If you

think you understand the actual goal, you could try rephrasing the response,

substituting a possible goal for their game-plan. If someone says, "I wish

we could ban all those political attack ads!" rather than lecturing them about court

decisions or freedom of expression, one possible response is, "It sounds

like you are really frustrated by attack ads and want factual information to

help you make an informed choice. Is that correct?" This response

recognizes the concern about attack ads and transforms the game-plan of

banning attack ads into a goal of factual information. Once you both understand

each other’s actual goals, is there common ground? If so, you can start exploring game-plans.

How many ways are there to frame this discussion? Is it about how much to spend, individual rights or responsibilities, or who is a victim or oppressor?

How could you reframe the discussion to focus on a shared goal such as equal opportunities or cleaning up a mess?

If you are not finding common ground, what might inspire you to

change your mind? If there is an alternative, would you want to hear it? What

might inspire you to seriously consider this alternative? If an alternative

might satisfy everyone concerned, would you be willing to shift your own

position? What might inspire others to shift their position?

Is it possible to split the group in a way that allows each smaller group to create their own solution?

What aspects of a solution can you control now? Is that enough to get started? We may have limited control

of a situation, but we can always control our own response.

If some participants are completely left out, is there a way they can get by while continuing to work on a more inclusive solution?

This is sometimes referred to as BATNA or Best Alternative to a Negotiated Agreement. A BATNA may give you a little of what you

want.

Are there enough existing advantages or benefits to justify going along with things as they are while exploring your own alternatives?

The worst case BATNA is finding a way to get by on your own, or perhaps with like-minded allies,

after others refuse to cooperate.

|