Thoughts about Thinking

Updated Mar 5th, 2025

-

Fact or Opinion?

-

Explanation or Excuse?

-

Common Sense or Nonsense?

-

Open-minded or Empty-headed?

When someone says, "Be reasonable!" sometimes they mean "Abandon your principles and beliefs and agree with me!"

These topics explore other options.

A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little

statesmen and philosophers and divines.

Ralph Waldo Emerson

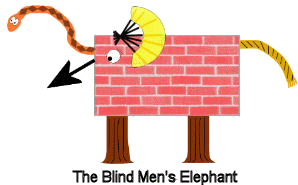

The Blind Men and the Elephant

by John Godfrey Saxe

It was six men of Indostan

To learning much inclined,

Who went to see the Elephant

(Though all of them were blind),

That each by observation

Might satisfy his mind

The First approached the Elephant,

And happening to fall

Against his broad and sturdy side,

At once began to bawl:

"God bless me! but the Elephant

Is very like a wall!"

The Second, feeling of the tusk,

Cried, "Ho! what have we here

So very round and smooth and sharp?

To me ’tis mighty clear

This wonder of an Elephant

Is very like a spear!"

The Third approached the animal,

And happening to take

The squirming trunk within his hands,

Thus boldly up and spake:

"I see," quoth he, "the Elephant

Is very like a snake!"

The Fourth reached out an eager hand,

And felt about the knee.

"What most this wondrous beast is like

Is mighty plain," quoth he;

" ’Tis clear enough the Elephant

Is very like a tree!"

The Fifth, who chanced to touch the ear,

Said: "E’en the blindest man

Can tell what this resembles most;

Deny the fact who can

This marvel of an Elephant

Is very like a fan!

The Sixth no sooner had begun

About the beast to grope,

Than, seizing on the swinging tail

That fell within his scope,

"I see," quoth he, "the Elephant

Is very like a rope!"

And so these men of Indostan

Disputed loud and long,

Each in his own opinion

Exceeding stiff and strong,

Though each was partly in the right,

They all were in the wrong!

Moral:

So oft in theologic wars,

The disputants, I ween,

Rail on in utter ignorance

Of what each other mean,

And prate about an Elephant

Not one of them has seen!

Anticipate and Prepare, or Wait and React?

In the beginner’s mind there are many possibilities; in the expert’s mind there are few.

Shunryu Suzuki

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.

John Muir

For every complex problem, there is a solution that is simple, neat, and wrong.

Henry L. Mencken

Fools rush in where angels fear to tread.

Alexander Pope

Young children have fanciful solutions to many problems. Their parents might

encourage imagination but hopefully they would never let their child jump off a tall

building with only an open umbrella to slow their fall. The parent’s

explanation to the child might range from "because I said so" to an experiment

dropping a fragile, heavy object attached to an open umbrella and observing what

happens.

Leonardo da Vinci was an incredible artist and made detailed drawings of

creative contraptions for flying and working underwater. Anyone actually

using one might not survive as the devices ignore unforgiving scientific

principles.

Science fiction stimulates our imagination and entertains us. It can be fun

and inspiring to imagine endless possibilities of faster-than-light space

travel. If the story is compelling, we may not care how warp

drive works or how a submarine could withstand the water pressure 20000

leagues under the sea.

Murder mysteries may

begin with clues that point to a particular suspect. Other characters

may demand this person be immediately arrested and punished. The true culprit is only revealed after a

determined detective sees some troubling loose ends and digs deeper. It is easy for readers or observers

to simply enjoy the bumps, twists, and turns of a well-told story without becoming emotionally invested in a particular outcome.

Situations that impact us directly are more difficult, but it is still important to occasionally take

a step back, listen to others, and look for alternate paths that may lead to a different conclusion.

An untrained person might make a beautiful bridge that collapses from the

weight of several heavily loaded trucks. An experienced civil engineer might

build a sturdy bridge but overlook ways to make it more beautiful. Would you

want your children to volunteer if the bridge-builder says "I don’t know how

much weight this bridge can support. Let’s send some cars across and see what

happens. If any cracks appear, I’ll slap on some duct tape."

How many safe crossings would you want to see before crossing yourself?

What if each crossing causes a little more damage, bringing the bridge closer to collapsing?

Is the builder entitled to believe duct tape can fix any damage to the bridge and that

talk of strong beams, cables, and rivets is self-serving propaganda from the greedy military-industrial complex?

We will not all make fundamental discoveries or invent something that changes

society, but we can share by understanding to the best of our ability, and by

recognizing that each important discovery or invention was influenced by many

who came before and contributed in some way. We can observe, wonder, and learn

from others who know more. An artist might not know how to build a sturdy

bridge but could inspire an engineer to explore ways to safely make a bridge more beautiful.

A science fiction story might inspire a physicist to

seek solutions to tasks previously considered impossible.

What about those who make laws or otherwise influence society? Might there

be unintended consequences? Can we fix it with duct tape? What should we expect from our elected

representatives?

You are Wrong! I Win!

When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the Universe.

John Muir

For every complex problem, there is a solution that is simple, neat, and wrong.

Henry L. Mencken

Don’t throw out the baby with the bathwater.

Reducing complex issues to two mutually exclusive options may seem simple and convenient.

-

If it is not black, does that mean it must be white?

-

If you tell a child not to hit, does that mean biting or kicking is OK?

-

If I can find a tiny fault in anything you say, does that prove I am completely right?

-

This situation requires immediate action. If a proposed solution provides immediate action is that solution automatically right?

-

This idea might not be the best, but it is not the worst either. If an idea is not the worst, is it automatically good enough?

-

If you cannot prove an idea is impossible, is it automatically reasonable?

Life is often more complicated. We prioritize to-do lists and rank colleges, homes, and job offers. Sometimes

comparisons are easy. Sometimes different aspects of the issue seem contradictory or overlap, and we need to look deeper:

-

This one has a good ... but that one has a better ....

-

If I settle for ... now, I might struggle later with ....

-

Is a proposed fix temporary or likely to need constant attention and adjusting?

-

If a solution needs more ... now, will it likely need less ... later?

-

Am I overlooking something that might make me regret my decision later?

-

How easily could I change my decision if I am not happy with it?

-

Would discussing options with friends or expert advice help me make a better decision? Why or why not?

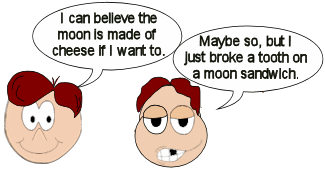

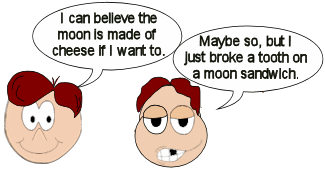

Open-minded or Empty-headed?

If you leave your mind wide open, others may fill it with trash.

An open-minded person is receptive to new ideas but need not embrace all ideas equally. It is

important to consider any evidence supporting the new idea, but equally important to look for contradictions with other

well-established concepts. If there is very little evidence either way, an open-minded person might simply take note of

the new idea, but reserve judgment until more compelling evidence turns up. If the new idea contradicts competing

concepts, the open-minded person might simultaneously reevaluate the old idea and analyze the new before choosing one

over the other. Several questions might help:

-

Does one option better solve existing problems?

-

Is one option more consistent?

-

Is one option more easily applied to a broad range of similar problems or facts?

-

Does one option rely more on special cases or have additional limitations?

-

Does either option lead to other useful conclusions or solutions?

-

Is either option unnecessarily complex?

Accepting an idea only because it is new, different, or emotionally satisfying might be just empty-headed.

Why Ask Why?

Discovery is seeing what everybody else has seen, and thinking what nobody else has

thought.

Albert Szent-Gyorgi

Millions saw the apple fall, but Newton asked why.

Bernard Baruch

Joy in looking and comprehending is nature’s most beautiful gift.

Albert Einstein

The cure for boredom is curiosity.

There is no cure for curiosity.

Dorothy Parker

I keep six honest serving-men,

They taught me all I knew;

Their names are What and Why and When

And How and Where and Who.

Rudyard Kipling

The larger the island of knowledge, the longer the shoreline of wonder.

Ralph W. Sockman

"Because it’s there" will probably satisfy the naturally curious. Asking

"Why?" can lead to hidden inner beauty, deeper understanding, and enhanced appreciation. One can look at the

night sky and see little twinkly lights, but telescopes reveal beautiful gas clouds, swirling galaxies and other

planetary systems. Each new answer often leads to previously unimagined questions, marvels, and mysteries.

If someone refuses to listen to music because they listened once and hated it, you might

encourage them to listen to other types of music, hoping they’ll find something they really enjoy. You might try to

educate them by sharing things you enjoy about your favorite music. We can’t all discover life-enhancing scientific breakthroughs, but we can share

in the process by learning and understanding. Science isn’t just grammar and spelling, but also poetry and literature.

Ignorance is not bliss when something goes wrong. You may find yourself in a precarious

situation where nothing you try helps, or at the mercy of someone who merely claims to know, which can get quite

expensive. Learn enough to ask the right questions. Without some knowledge, it is difficult to choose an advisor or even know which advice to trust. Nobody can

be an expert in everything, but it helps to at least know something about professional certifications and licenses, and

qualified, impartial third parties who can recommend an appropriate expert.

The Cockroach Syndrome

Patriotism is the last refuge of a scoundrel.

Sam Johnson

We can easily forgive a child who is afraid of the dark; the real tragedy of life is

when adults are afraid of the light.

Plato

Many people are open to listening carefully, trying to understand, and shifting their own position in response to new information.

Cockroaches scurry for a dark hiding place when someone turns on a light.

People sometimes respond in a similar way when questioned or challenged about

something they said. Rather than addressing questions or concerns with factual information, they

withdraw, dodge questions, or make accusations. There may be an underlying belief that all

opinions should be accepted without question, or that

any belief or opinion that has a tiny amount of validity should be considered equal to any other.

Be skeptical of things that only "work" when no one is looking.

Explanation or Excuse?

Explanations

-

begin with impartial observations or supportable facts and work toward conclusions in a

logically consistent way. The starting point doesn’t require absolute certainty but should be based on the best

available information.

-

usually have some predictive value - if the initial situation or proposed cause arises

later, a similar outcome should be likely.

-

consider all relevant information.

Excuses

-

usually start with an actual outcome or desired conclusion and work backward to a cause

(usually unconnected with the person offering the excuse). Any convenient or contrived reasoning may be used with

little regard for quality or consistency.

-

don’t often work "forwards" - next time there may be a totally different outcome

with no reasonable explanation for the change.

-

often ignore information that could invalidate the excuse (the

cockroach syndrome), or avoid the actual starting point by only

backtracking to an intermediate step that shifts blame to someone else.

But It is Only a Theory

So is gravity. Gravity happens to be a very strong theory supported by substantial evidence

but even after extensive research, some fundamental details remain elusive. In science, a hypothesis may be little more

than a hunch and is often the starting point of an investigation. Once the research is done and the results are

verified, the conclusions are combined with everything else that is known with any certainty to form a theory. As

observations and experimental evidence accumulate, the theory becomes more certain. Incomplete evidence becomes

stronger in the absence of contradictory evidence and reasonable alternate explanations.

There is always room for doubt but take care not to fabricate special circumstances just to

make a conclusion seem wrong or less useful. What are you trying to accomplish by doubting? Is there a fact or

assumption that could be tested? Do you want an

excuse to believe something else?

Are -- better at -- than -- ?

Facts are stubborn, but statistics are more pliable.

Get your facts first, then you can distort them as you please.

Mark Twain

There are three kinds of lies: lies, damn lies, and statistics.

Benjamin Disraeli

It can be difficult to find someone who is exactly average. Unlike Garrison Keillor’s Lake

Wobegone, where "all the children are above average", if someone is above average, at least one other person

in the group must be below average. If 3 people in the same group score 91, 94, and 10 on a test, their average score

is 65. 2/3 are well above average and have a high score. None are close to average. 3 people in another group might

take the same test and score 85, 80, and 84 for an average of 83. All are good scores and close to average. Which group

is better? If you could choose one person, would you choose based on the group they are in, or based on their personal

score? If you could choose 3 people, would you choose all 3 from the same group? When would you need to know which

group is better?

Is Anything Possible?

It depends on what you mean by possible. We can say it is possible to flip a coin 100,000,000

times and get heads each time. In this case, all we really mean is that it is not impossible. It doesn’t violate any

known laws of science, but do you really want to spend your time trying to confirm this possibility? A coin toss is

often considered a fair way to randomly choose between two options. This is based on knowledge that the coin is balanced well enough to avoid a preferred outcome, and by

observing many coin tosses by many people, and counting the number of heads and tails over time. Without doing any

calculations, we can flip a coin many times in succession and observe that the number of heads and tails isn’t always

the same. This suggests that it is possible to get 100,000,000 heads in a row, even though the probability is very

small. This randomness is generally accepted, in part because it has been observed so often, and the observations are

consistent. These observations make it easier to accept the possibility of 100,000,000 successive heads even though

it is not likely anyone will ever see it happen.

Someone might say it is possible that people are manipulated by a mind-control ray from

aliens orbiting the earth in a flying saucer. Like the possibility of getting 100,000,000 heads in a row, this doesn’t

seem impossible. Life elsewhere in the universe doesn’t violate any known laws of science, and beings from another

planet might develop the technology for remote mind control and space travel. In addition to the "not

impossible" test, we should also consider relevant observations and ask a few basic questions:

-

Has the presence of flying saucers been convincingly documented?

-

How does the behavior of those supposedly subjected to the mind control ray differ from the

behavior from others?

-

Do the brains of those supposedly controlled by the ray have any observable physical,

electrical or chemical abnormalities?

-

Was there ever a time when the aliens weren’t using their mind control ray, and if so, were

the behaviors attributed to the ray ever observed then?

-

Do the aliens ever stop using the ray, and if so, does anyone’s behavior change?

-

Can the ray be detected or measured?

-

Are there any other possible explanations for the observed behavior?

The answers to the above questions don’t necessarily make it impossible but might

substantially reduce the probability. Just as you probably don’t want to devote your life to tossing a coin until you

get 100,000,000 heads in a row, is it productive or useful to spend time wondering about mind control rays from flying

saucers?

If you admit that one thing is possible, will you also admit that alternatives are also

possible? Perhaps people here on earth are manipulating the minds of the aliens, making the aliens think

they are successfully using a mind-control ray. Should we prefer one possibility over all others?

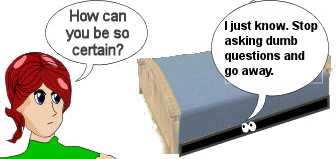

Will It Ever be Wrong?

People sometimes feel confident or complacent "knowing" that they are right, but

logically sound reasoning requires the possibility that new observations or necessary assumptions might prove the

conclusion wrong. A thorough, impartial evaluation of all supporting evidence is important, but it is often useful to

also ask, "What would persuade me to change my mind?" If the answer is, "Nothing will ever change my

mind", the credibility of the conclusion is questionable and implies

a refusal to consider all available evidence (the cockroach syndrome), and

could be the result of making excuses rather than impartially seeking the best

possible answer. Another useful question to ask someone with a belief or opinion that seems to be permanently

entrenched is, "Was there ever a time you believed something different?". If so, what changed? If not, how

and when did this belief or opinion originate?

Clinging to an insupportable conclusion may appear to minimize inconvenience or disruption

of an established belief, but also slows progress, as it usually has no practical value or useful consequences. The

truth (or best possible answer given the currently available information) usually provides a solid foundation to build

on and may help support or refute other conclusions. Remember the old advice, "Never argue with a fool".

They do not respond to reason and drag you down to their level - after a few minutes, it is hard to tell

who is the bigger fool.

Will your sanity check bounce?

Reality is that which, when you stop believing in it, does not go away.

A little experience often upsets a lot of theory.

The price of wisdom is eternal thought.

Frank Birch

It is often tempting to generalize based on one or two specific instances, and sometimes

that is all you have to go on, but usually that is just the beginning. Once you think you have a valid conclusion, try

working it "backwards" to see if you can get back to the specific observations that got you started. Some

people refer to this as a "sanity check" or a "reality check" because it scrutinizes the conclusion

to make sure it is still consistent with all actual observations.

-

Does it work in every possible situation, or do you have to make exceptions in some cases?

-

Can it reliably predict the outcome of all similar situations, or does it only work

sometimes?

-

Are there unintended consequences or contradictions with related concepts or observations?

If there are exceptions, can you find a way to predict which future situations will follow

the "rule" and which will be an exception? If your sanity check bounces, further refinement might be needed,

or you might have to throw it out and start over.

Don’t Win the Wrong Argument

A fanatic is one who can’t change his mind and won’t change the subject.

Winston Churchill

Hain’t we got all the fools in town on our side? And hain’t that a big enough majority

in any town?

Mark Twain

It might seem tempting to bolster a case with personal attacks, or by redirecting the

discussion, but usually that is just trying to win the wrong argument.

Vilifying those on the other side of a dispute may be simpler than intelligently discussing

complex issues, but even a fool can repeat a noble truth. Accusing someone of foolishness might incline others to

believe that the person in question is indeed a fool but doesn’t necessarily mean that the persons words or actions

were foolish in themselves.

Someone might claim that roofers

have the best/worst job in the world. They get lots of time off because they can’t work in the rain, but they don’t

make much money because when it is not raining, people don’t need roofs. Such observations could easily be the source of

an endless argument. One person might explain all the great things that could be done with lots of free time, while an

opponent goes on about the hardships endured by those with low incomes. They could each produce ever lengthening lists

of people who enjoy/endure the situation, and specific accomplishments/suffering resulting from such a job. Each claims

victory by overwhelming evidence, but nothing gets resolved. They each argue about only one aspect of the job and make

no effort to address the other’s concerns.

Follow the Leader

Nearly all men can stand adversity, but if you want to test a man’s character, give him power.

Robert G. Ingersoll

Loyalty to the country always. Loyalty to the government when it deserves it.

Mark Twain

-

Did the group form around the leader or did the leader emerge from within the group?

-

If the group formed around the leader, did the leader coerce the group in any way?

-

Do you follow the person or what the leader stands for?

-

How well do each of the leader’s goals or methods align with your interests?

-

What are you willing to sacrifice to get the things you want?

-

What principles guide or inspire the leader?

-

Which of the leader’s guiding principles do you apply to yourself?

People may belong to cliques, gangs,

religions, cults, families, societies, companies and fan clubs, each with its own purposes and goals. Sometimes

there is a common goal or a greater purpose. Other times, simply belonging might be enough, in which case there is little

need for a strong leader. Understand what you want and expect, and ask questions if the leader’s methods or objectives

conflict with your personal beliefs or goals. If the leadership requires you to accept things you do not like as a condition

of getting something you want, are the leader’s goals truly aligned with the group’s goals? Would a different leader be better?

Perhaps it is time to reconsider the group goals and choice of leader.

Practical Idealism

Those who say something cannot be done should not interfere with those actually doing it.

Idealistic goals may get dismissed as noble, but not practical. Idealism can be admirable

when striving toward a lofty goal, but an oversimplified agenda may be disruptive if based on a limited understanding

of the problem or the means of solving the problem. We can accept that some things exist right now, but we don’t have

to accept them as inevitable, necessary, or desirable. Don’t give up on the ideal as an ultimate end. It might not be

instantly available but think of the "practical limits" as obstacles requiring long-term effort. Before

settling, consider:

-

Do unmet needs require immediate action?

-

What are the consequences of not acting now?

-

Can controversial sections be considered separately?

-

Could there be unintended or irreversible consequences?

-

How easily can changes be made later?

-

Does a compromise get you closer to your ideal goal?

A Compromised Solution

Should you accept something undesirable as a condition

of getting something else you want? Mutual backscratching should not involve anything sharp or pointy. If both sides

are giving up something in exchange for something they don’t want, try to separate the issues. Holding one issue

hostage by linking it to an unrelated issue in the name of compromise might not

serve everyone’s best interests. Don’t make it about winning, especially if others are affected by the decision.

Calculating Credibility

There are so many claims about so many subjects, it is sometimes difficult to know who or

what to believe. Here are some suggestions.

Start with a thorough, impartial evaluation of all available evidence:

-

What qualifications or abilities are required to do such an evaluation?

-

Who determines those qualifications and why?

-

Who has those qualifications?

-

What percentage of qualified people are for, against, undecided, or neutral?

Is there a possible ulterior motive such as:

-

ego or emotional attachment

-

greed

-

stubbornness or arguing just for the sake of argument

-

personal comfort or convenience

-

a desire to bait or emotionally inflame others

-

just making excuses

Are the claims only relevant to one special case or can it be generalized to other things?

If a position is based on cost or safety, is the same degree of safety or cost-consciousness expected from everything,

or just this one issue?

If there is significant evidence for more than one position (or insufficient evidence for

reasonable certainty):

-

What are the possible consequences of being wrong?

-

What are the expected early warning signs of failure?

-

How easily could errors be detected and corrected?

Are reasonable objections accounted for or just dismissed or ignored by changing the subject

(the cockroach syndrome)? Does explaining away objections require adding

more assumptions or greater complexity?

What circumstances or conditions led to the conclusion? Was it paid for, and if so, by whom?

Is the conclusion reevaluated as new information becomes available?

Investigating the Investigators

Thorough investigations can provide valuable lessons about what happened, how or why it

happened, and what might help to better control such situations in the future. Sometimes the results of these

investigations contradict earlier accounts, which might warrant an investigation of the investigators. Assuming the

investigation was impartial, some potentially useful questions are:

-

Did the later investigation consider all information previously available?

-

Did the later investigation have additional information not previously available?

-

Were earlier accounts or decisions reasonable under the circumstances when based on

information available at the time?

-

Was there bias by any investigators which caused them to overlook or excuse certain things?

It could turn out the earlier actions or decisions were reasonable under the circumstances,

and those involved would agree that with more information or resources, things would have been different. Improving the

outcome of future similar situations might require access to better information or resources.

If the investigation reveals mistakes or poor decisions, perhaps better training or people

with different skills would produce a better result next time.

If bias was suspected, was any evidence found such as ignored or dismissed observations?

If those involved simply refuse to accept the results of the investigation, perhaps they are

just making excuses.

Burdensome Proof

A lie can travel half way around the world while the truth is putting on its shoes.

A truth is not hard to kill and a lie told well is immortal.

Never let the truth get in the way of a good story.

Mark Twain

The first to present his case seems right, till another comes forward to question

him.

Proverbs 18:17

Give me a grain of truth and I will mix it up with a great mass of falsehood so that

no chemist will ever be able to separate them.

John Wilkes

Accusations are easily made and often difficult to disprove. If the accusation is hasty,

frivolous, or poorly supported, the accused shouldn’t have to spend time and effort disproving the charge, especially

if the accuser can just come back with yet another casual accusation. Sometimes, those accused simply respond with

accusations of their own.

In the name of "fairness" or "equal time" it might seem tempting to simply accept the

accusation and then ask the accused to disprove it. There is nothing fair or equal about it. An accuser could make a

casual accusation with little effort and no evidence, while the accused might need to invest substantial time and

effort gathering evidence and presenting a convincing defense. If the accusation is a generality, such as "this

person lies", or "this person is a thief", ask for specific examples.

Before seriously considering an accusation, demand more from accusers:

-

What is the source of your information?

-

Why do you believe this information is reliable?

-

Does the accused accept this information as accurate?

-

Why should we believe you rather than the accused?

-

Did you ask the accused for evidence that might disprove the accusation?

-

Did you consider all evidence suggested by the accused?

-

Can you summarize the defense of the accused?

-

Can you convincingly explain why any defense is either wrong or irrelevant?

This shifts the burden to the accuser. Now the accused may be able to quickly respond by

asking questions like:

-

Did the accuser talk to ... ?

-

Did the accuser read ... ?

-

How does the accuser explain ... ?

Now go back and ask the accuser to summarize the additional information suggested by the

accused and explain why it is wrong or irrelevant. If the accusation has little merit, accusers may give up

once they realize that the burden of proof is on them.

Can God make a rock so big even he cannot move it?

This question can be divided into 2 parts:

-

Can God make a rock of any size?

-

Can God not move a rock of any size?

The answer to either question could be "yes" or "no" so we have 4

possible combinations:

-

God can make a rock of any size and also move a rock of any size.

-

God can make a rock of any size, but not move rock of any size.

-

God cannot make a rock of any size, but could move a rock of any size.

-

God cannot make a rock of any size, and cannot move a rock of any size.

If the answers to question A and B are both "yes", then the answer to the entire

question is "yes". If the answer to either question A or question B is "no" then the answer to the

entire question is "no". Since question B is asked as a negative (Can God can not move a rock of any size)

only answer option 2 makes the answer to the original question "yes". The following table shows all

possible answers to the original question.

|

Can God make a rock so big he cannot move it?

|

God can move a rock of any size.

|

God can not move a rock of any size.

|

|

God can make a rock of any size.

|

No

|

Yes

|

|

God can not make a rock of any size.

|

No

|

No

|

Squirrels, trees and circles

Imaging walking through the woods and seeing a squirrel on an oak tree. The squirrel also

sees you and immediately scurries to the opposite side of the tree. You circle the tree trying to catch another

glimpse of the squirrel, but the squirrel is also circling the tree to stay on the opposite side. You are going around

the tree, the squirrel is also going around the tree, but are you going around the squirrel?

This answer doesn’t depend on logic so much as on careful definitions. You are walking in a

circle, and the tree and squirrel are always inside the circle, but you and the squirrel would always be facing each

other if the tree weren’t in the way. The word "around" could be understood either way, and the exact meaning

determines the answer to the question. If you understand "around" to mean that if the tree weren’t there, you

would see the squirrel from all sides (front, back, right, left) while walking "around", the answer is different than if you understand

"around" to mean that the squirrel is always inside the circle you are making with your footprints.

Absence of Proof and Proof of Nonexistence

Absence of proof could mean many things. It might seem tempting to assume that absence of

proof (or a limited understanding) implies impossibility or opens the door to speculation, but it really

depends on what else is known. A good place to start is to consider the plausibility of the original claim. There is no

proof of the Loch Ness Monster, yet it is not impossible. We might consider several things to estimate plausibility:

-

Loch Ness is difficult to explore.

-

New species are occasionally discovered.

-

There is an incredible diversity of life on earth.

-

Descriptions from claimed sightings are similar to known creatures, either living or

extinct.

So far, the existence of a Loch Ness Monster doesn’t violate any known natural laws or

principles, however the probability goes down with each new serious investigation:

-

Something that big isn’t easily missed.

-

Reported descriptions are most like known air-breathing creatures, which increases the

probability of surface sightings.

-

Animals reproduce and die, yet no remains or partial remains of dead monsters have ever

been found.

The above objections might be explained by small numbers of very shy monsters that die

instantly and immediately sink to the bottom where they quickly decompose, but now we are speculating about increasingly

unlikely circumstances. These secondary speculations must be subjected to the same scrutiny as the original claim. Of

course there is always room for doubt when the only argument against existence is a lack of reliable observations or an

inability to explain certain details which in themselves are not impossible.

Besides, people love a good mystery, and

the discovery of such a creature would be very exciting.

Proof of nonexistence is much trickier to deal with. In general, you cannot prove

nonexistence in any absolute way since one can always fabricate explanations for the lack of direct evidence or

observations. We can sometimes take an indirect approach and consider what else might be true if the subject of

investigation really did exist. We could assume that if there really were a Loch Ness Monster, it would

eat, reproduce and die. This leads to several conclusions:

-

There must be sufficient food in Loch Ness to support something that big.

-

If it breathes air, it must surface at regular intervals.

-

If it reproduces, there will probably be at least two.

-

When it dies, there will be remains.

If we could show that none of those things were true, that would greatly decrease the probability of existence.

Extraordinary Claims, Extraordinary Proof

It is often said that extraordinary claims require extraordinary proof. If your best friend

tells you that a neighbor has a pet pig, you probably know that some people do have pet pigs and might believe your

best friend without any further evidence. If someone tells you that a neighbor has a pet elephant, you would probably be

more skeptical, especially if you live in a city. You might think that perhaps it is a toy elephant, or something other

than a real live, eating, trumpeting elephant. If you are told that a neighbor has a pet unicorn, you should be really

skeptical. Even if you actually see a living creature with something sticking out of its forehead, you should still

suspect a hoax. You might want to hear from an impartial veterinarian, see the results of a DNA analysis, or

observe the creature reproduce in a controlled environment and verify that the offspring really are unicorns.

Keep it Simple

Things should be made as simple as possible -- but no simpler.

Albert Einstein

If it ain’t broke, don’t fix it.

Sometimes a cigar is just a cigar.

Sigmund Freud

A useful question is "What is the problem you are trying to solve?". Once you really

understand that, don’t fabricate a complex solution when a simple approach will get the results you want. If you see a

picture of something on the surface of Mars that resembles a primate-like face, explore the simple solutions before

jumping to conclusions about intelligent life on Mars. You might start by considering the size and contours of the

"face", to see if they are consistent with the results of geologic or atmospheric forces such as wind, water,

or crust movement similar to those on earth. Even a short hike in the mountains of earth often reveals natural

formations that resemble something else. Most young children can see all sorts of things in earthly cloud

formations. It is just a result of normal brain functions and an active imagination. If the simple solution checks out,

be very careful before seeking a more complex solution such as

intelligent life on Mars. Attributing an apparently natural feature to living creators quickly leads to some important

questions with no obvious answers:

-

Why didn’t entities with the technology to make such a large "face" leave other

traces?

-

Who was it made for? If it was made as a form of interplanetary message, they were advanced

enough to believe they might not be alone and probably would have left other evidence or signals.

-

What other technology would they probably have, and why isn’t there any evidence?

-

Why didn’t they make anything else?

-

How likely is it that they would resemble us?

Half a Loaf or None?

Before settling for half a loaf, consider if it is enough to be

worthwhile:

-

Will the matter be considered closed after getting only half a loaf?

-

Is the other half attainable in the foreseeable future?

-

At what point must the current system be scrapped and entirely replaced?

-

Will it create a false sense of security that might reduce future

development?

-

Would the money be better spent elsewhere?

-

Is there an urgent need that can’t be met any other way?

Don’t Read Everything You Believe

I respect faith, but doubt is what gets you an education.

Wilson Mizner

The price of wisdom is eternal thought.

Frank Birch

It is natural to associate with like-minded people, and having your opinions and conclusions

validated by friends, speakers or authors who share your beliefs can be very gratifying. It can also make people

so comfortable that they stop asking questions and no longer explore alternatives. Don’t overlook the importance

of an occasional, well-reasoned dissenting opinion.

A Second Opinion

The first to present his case seems right, till another comes forward to question

him.

Proverbs 18:17

How reliable is a first (and only) opinion? Many puzzles and brainteasers begin with a

plausible situation, proceeding step by step, only to end with a seemingly irreconcilable contradiction. Zeno’s Paradox

is a famous example which concludes that motion is impossible by arguing that to reach any point, you must first pass

the half-way point, the half-way point to the half-way point, etc. ultimately passing through an infinite number of

intermediate points. Since passing through an infinite number of points would take forever, motion itself is therefore

impossible, or at best an illusion. An isolated argument may seem reasonable at first, but is it really solid?

-

Was any relevant information ignored, dismissed, misunderstood or distorted?

-

Are unrelated things lumped together as if they are the same?

-

Are further distinctions needed between similar facts or concepts?

Zeno’s Paradox ignores the fact that as you increase the number of intermediate points, the

distance between the points (and the time to move between adjacent points) gets smaller, ultimately approaching zero as

the number of points approaches infinity.

A second opinion from someone reaching a different conclusion can help locate flaws in the

original argument, but the second opinion should be scrutinized as carefully as the first.

-

Do they both start with the same facts or observations?

-

Do they justify alternatives, or just say the other is wrong?

-

Does one replace an unknown with a different unknown?

Sometimes there just isn’t enough information to be certain and even

experts will disagree.

None of the Above

"If we don’t use my idea right now, the situation will spin out of control with

disastrous consequences!"

The intended implication is that only the proposed solution will prevent a catastrophe, but

there are really 2 separate statements:

-

Without intervention, the situation may develop on its own with potentially unpleasant

consequences.

-

There is at least one possible solution.

These two issues could be considered separately. Is action really required right now, and if

so, what kind of action would be most appropriate?

-

Will the proposed solution fix the problem permanently?

-

How likely are side effects?

-

Is it practical?

-

Will everyone support it?

If people disagree on significant aspects of the solution, more options would probably be

helpful, especially if the proposed solutions are mutually exclusive.

"If I don’t get $6000 right away, my life is ruined!"

This might start an argument with one person demanding $6000 and another refusing to provide

it. Exploring the matter further might suggest alternatives.

"Why do you need the money?"

"To buy a car."

"Why do you need a car right now?"

"So I can get to work."

Someone started out by asking for $6000 but really wants transportation to work. This new

information opens up more possibilities:

-

Is another job available closer to home?

-

Would moving closer to work help?

-

Is another method of transportation available?

-

Would a cheaper car provide adequate transportation?

Finding alternatives may be difficult, but some possible questions are:

-

Is there an underlying problem (needing money to buy a car to get to work)?

-

Are there several aspects that could be considered separately?

-

Can any consequences be considered separately?

-

Is this problem similar to another that has already been solved?

Are Logic and Truth Relative?

Truth and logic are subject to certain restrictions and preconditions. It is often said that

the shortest distance between two points is a straight line, but if you walk from your house to a friend’s house,

you are really walking on the surface of the earth (a sphere). Traveling a truly straight line might require

burrowing through the earth. This might be the shortest distance but is less efficient in terms of travel time

or required effort. We might amend the old adage to say that it is only practical on a flat surface. Even then we might

want to further clarify what "flat" really means, since the limits of our perception might make the earth appear flat unless we observe

it from space.

Apart from carefully defined conditions, be very skeptical of any claims of variations in

"truth". A good test of questionable claims would be to look for practical applications of the alternate

"truth". If someone claims that "For me, 2+2=5. That is my reality", put that claim to a practical

test. You get a stack of $1 bills, and have the other person get a stack of $5 bills. You give the other person $2,

then another $2, and in return you get $5. Keep the exchange going all day.

Are All Opinions Equal?

Everyone is entitled to form opinions just as everyone is entitled to choose how to behave. Some choose to behave in ways that benefit others. Some choose

different behaviors. Are all the ways people can behave equal?

There are many types of opinions. An opinion may be subjective or objective, and

may be based on idle speculation, rumor, wishful thinking, what-ifs, direct observations, expert knowledge or other things. A subjective opinion might involve color or style of

clothing, although there might be other considerations if one is dressing for a job interview or other situation where

the impression given by the clothes might have consequences.

Objective opinions can be compared and evaluated based upon underlying observations or factual

information. Objective opinions often start with an observation and a plausible cause and effect relationship that leads from

the observation to something else.

Someone could say "I believe the moon is made of

swiss cheese. That is my opinion and I’m entitled to it." It is in fact an opinion, and with a little imagination the moon does have a slight resemblance

to swiss cheese, but how useful is this opinion? How did a giant, spherical piece of cheese end up orbiting the earth? This person

could go on to speculate about a giant, invisible, cosmic cow and cheesemaker but no observations or plausible explanations support either.

Would an invisible cow give invisible milk? Now this person must speculate about how the milk or cheese became visible.

Where is the cow now? Where did it come from? What does it eat? Any answers offered are most likely totally unrelated to a slight resemblance between the moon

and swiss cheese which is the foundation for the opinion. Does this person refuse to answer

or get angry because you ask questions or want to explore alternatives?

If this person traveled to the moon, would they pack a lunch or just plan on scooping handfuls of cheese? This opinion has

practical consequences which can be tested to judge the quality of the opinion.

Do All Opinions Deserve Equal Time?

A fanatic is one who can’t change his mind and won’t change the subject.

Winston Churchill

Some opinions have been so thoroughly analyzed and discredited that they’ve lost any claim

to equal time. This isn’t censorship - it’s just good time management. That’s not to say that the holders of those

opinions should suffer any kind of retribution simply because they hold insupportable opinions - they’re just not

entitled to an audience gathered by others for a different purpose. Stubbornly held, discredited opinions contribute nothing to a serious discussion and won’t

change the final result - they just get in the way. Granting equal time in geography class to the claim

that the earth is flat just takes time from more important topics. A discussion of the science and observations

throughout history that lead up to the final acceptance that the earth is a sphere, and why some people once assumed it

was flat, could be a useful lesson. Spending time refuting fabricated, distorted or misinterpreted

"evidence" of a flat earth is not, especially when people cling so stubbornly to their opinions that no amount

of explanation or evidence will change their mind. One must be especially careful with children as they are not always

capable of fully grasping the logical thought processes and underlying science that led to the overwhelming rejection

of certain concepts. Equal time could just confuse them and leave them with the idea that all possibilities

are equally likely, and therefore equally valid.

When you suspect that someone is stubbornly clinging to an unsubstantiated opinion, you

might ask why they hold and perpetuate that opinion. Some other reasons to consider are:

-

to make money by manipulating others

-

to justify hate

-

to argue, often just for the sake of argument

-

to bait, or emotionally inflame others

-

for emotional security, comfort, or convenience

Does this opinion have any useful consequences? How does believing that the earth is flat

help while traveling around the world? How does such a belief help to understand or accomplish anything?

When Scientists Disagree

It’s not unusual to hear something like "Most scientists support my position that

...", only to hear someone on the opposite side of the dispute say exactly the same thing. If the dispute is to be

settled by means other than popular vote, we need to look deeper into what scientists are believed to be saying. There

are several possible reasons someone might mistakenly believe that most scientists support their position, including:

-

Ignoring scientists whose conclusions disagree

-

The "scientists" (often nameless) are not truly experts in the field and may have

reached an insupportable conclusion.

-

The scientists were hired to "study" the issue, with the understanding that a

particular conclusion was desired.

-

The scientific conclusions were misunderstood or misrepresented.

These possibilities suggest several questions to ask:

-

How were the scientists chosen? Were they chosen because of their conclusions?

-

Are the scientists highly regarded by other scientists in the same field?

-

What qualifications were required of the selected scientists?

-

Under what circumstances did the scientists first reach their conclusion?

-

Who paid for the study?

-

What percentage of all scientists in that field were considered?

-

Do scientists in the field generally accept any additional interpretations?

-

Is the issue likely to be an emotional one for the scientists involved?

It’s possible that even after getting reasonable answers to all the above questions, the

dispute remains. Science thrives on controversy and uncertainty. Sometimes there just isn’t enough information and

additional research may help clarify things. Also, scientists sometimes make mistakes, but the scientific process

itself tends to correct any mistakes and approach the truth as new, reliable information becomes available.

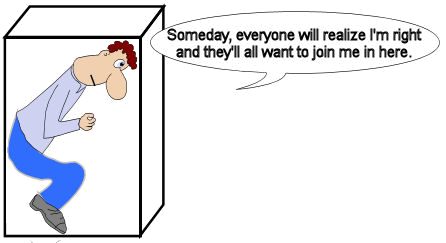

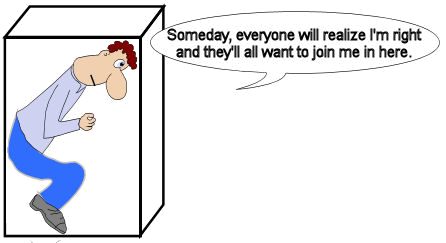

The Shrinking Box of Ignorance

Ignorance is not a point of view.

Mimes sometimes perform a routine where they pretend to be inside a slowly shrinking box.

The top and sides of the box gradually close in, forcing the mime to contort to fit the ever-diminishing space. People

who stubbornly cling to an assertion despite mounting contradictory evidence place themselves inside a box of

ignorance. Each new conflicting fact shrinks the box, forcing the occupant to further contort their beliefs to fit the

limits imposed by the box. The mime simply steps out of the box at the end of the routine. Those dwelling in a box of

ignorance often choose to remain inside, becoming ever more confined until the constraints prohibit them from

accomplishing much of anything.

Random Determinism

We often speak of random events but what do we really mean? Often, we mean that the results

cannot be reliably predicted for if they were truly random, then even perfect knowledge would prevent a perfect

prediction. When we flip a coin or toss dice, we can calculate the probability of particular outcomes, and test those

calculations with thousands of trials, but a truly random outcome would violate the laws of physics. Coins and dice

have a specific shape, mass and center of gravity, and should respond in a consistent way to a force of known

magnitude, direction and duration. The "randomness" comes in because the forces are so subtle and complex

that we can’t know all the details with any certainty. Oil or sweat from fingers changes the center of gravity, a

slight breeze from a fan, air conditioner or open window affects the total force, and the exact force and direction of

the throw depends on variations in muscle contractions. With perfect knowledge of all possible variables,

we could predict perfectly. In the absence of that perfection, the best we can do is to say that the outcome is random

and assign a certain probability to each possible result.

None of this eliminates the possibility of truly random occurrences, but there’s always the chance that with just a little more

information, a seemingly random event might become predictable.

|